Episode Intro

Since 1978, Sean L. Young has (always) had a passion for languages. He has studied, learned, and taught over 60 languages, and has achieved conversational fluency in half of them. That is so impressive, to be honest. He is the founder of Young's Language Consulting and the creator of the Rosetta Stone Challenge and the Speak Up Language series. In the 1990s, he was invited to teach in schools and universities in Europe, and later, with the help of the internet, he expanded his teaching throughout the world. After retiring in 2023, he's been working as an educational consultant, helping to change how languages are taught and learned, and I am very, very pleased to welcome him here on the Cultivate Podcast as my first guest.

Michelle:

Hi Sean. Very nice to have you here today.

Sean:

Good to be here.

Michelle:

Yeah, I know. I'm in the Washington DC area right now. Where are you calling from?

Sean:

I am in Dallas, Texas. Well, more specifically a suburb Garland,

Michelle:

Texas. Yeah. How's the weather there?

Sean:

Right now? The sun is shining, but it's deceivingly cold. It's about 50, 60 degrees right now.

Michelle:

Oh, well, that's still warmer than here. We had complete snow yesterday. I don't know if you saw on my Instagram, but I basically was not prepared. It was freezing. It was really cold.

Sean:

Yeah, I saw that. The snow swirling around and everything. I miss my New York days.

Michelle:

Oh, yeah, yeah. I am not a fan of cold weather, so I basically, yeah, I am not prepared for this, you know what I mean? I am not ready for winter at all.

Sean:

Oh, so then you would not have liked it if you were with me when I was in Moscow. It was 40 below zero.

Michelle:

No, no.

Sean:

The wind chill was 90 below.

Michelle:

That's when Celsius and Fahrenheit meet, I think, right? On the scale?

Sean:

I don't care what they say. It's cold!

Michelle:

It's cold. Exactly. Well, thank you for joining me today. Thank you for taking the time. Of course. And you are my first guest, which is very cool. I've already done your introduction, but I'll also let you kind of speak and introduce yourself. Who are you? Tell us about your amazing life and career!

Sean:

Well, I wouldn't know about “amazing,” but basically, well, with languages. It started way back in 1978. I was 13 years old and in middle school learning about ancient Egyptian, and the teacher showed a picture of the Rosetta Stone. Oh my goodness. That fascinated me to no end. I mean, the writing and everything like that. I loved it. And so that gave me a thirst for what more do I want to know about it? I went to the libraries. Well, I couldn't go to the college library. I was too young then, but I learned everything I could about ancient Egypt, and because of that, it just kind of snowballed.

Sean:

I started learning Ancient Greek, and then when I went to high school, (where) I'm learning Spanish and French and Latin. I meet all these foreign exchange students, so I got to learn their languages too. So by the time I graduated, I had knowledge of or learned about 21 languages.

Michelle:

Wow. I mean, this is during a time, and forgive the reference, it's not meant to put any sort of date on this, but it's essentially to say that Google didn't exist back then, and certainly the idea of having software or applications or things that were really adapted for facilitating learning… you didn't have any of that.

Sean:

Oh, no. That stuff came around in the 1990s. We're talking 1984 when… language learning was tough. I mean, a lot of the books back then were more theoretical and academic style writings, but hard to learn a language. But I toughed it out and I had to find a way to do it.

Michelle:

So then how did you do it? I'm curious to know how you approached it, especially as a teenager. What did you do? Did you go to the library and check a bunch of books out, or how did you handle it?

Sean:

Yeah. The librarians actually knew me by name.

Michelle:

Yeah, great!

Sean:

They see me walk in, “Hey, Sean, we got some new books for you!” But what I did was I basically was learning language as a traditional way, but in high school I had this Mexican girlfriend friend, and she was telling me about how Spanish words and English words, some similarities, like in -TION, like nation in Spanish, is -CION. And it is like, oh, that's interesting. So we started thinking what other similarities are there with them in Spanish and English? And then I went to the library. I found a book called The Mother Tongue by Lancelot Hagman. Oh my goodness. That told me a whole bunch of stuff about how with just by knowing English, it gives little clues and tricks and hacks and everything so you could learn, well, yeah, learn about 13 different European languages to that. That was my Bible. That was it. And from that, it just snowballed. And so what I did was tried. I decided to forget all this traditional language, learning everything I've learned about it, forget it. So I started looking at the languages themselves. This word is teaching me what I just picked a language apart until eventually and through the years, it took me about 10 years to make a system that allowed you to learn a language in less than a year, any language. And I still use it today on myself and my students, and it's based upon what I call power charts. But I originally called this thing the Rosetta Stone Challenge in honor of the Rosetta Stone that got me started!

Michelle:

Yeah, yeah, the OG, I suppose, because I also remember seeing and learning about it. And just at that time, I would not say that I personally had a deep interest in learning new languages, but I just remember thinking, oh my gosh, this is so incredible. From not even centuries at that point. You're just… it's the ancient, ancient world, and you realize we are just so lucky that we can communicate today. We are so lucky that we have resources today. We are so lucky to be in the world where we are. And so I love that you paid homage to this. I also love that you found your own way to figure out, I don't know. Again, during a time where it was not impossible, so it's not like it could have been worse, I think, however, I hear a lot of people in this day and age complaining, and these are people of all ages, backgrounds, complaining about the fact that they don't have enough resources. And in the back of my head, I'm always like, but it was so much worse before, this is the best that has ever existed. Right?

Sean:

Oh yeah. Oh yeah. I mean, how many trips I took to the library… The city I grew up in is a small city in New York, upstate New York, but there were communities of German, Polish, Ukrainian, Chinese, and Japanese. So I was able to get those figured out, those languages figured out by doing that. But other languages, I had to go to the library or not learn what I wanted to learn.

Michelle:

Yeah, I'm kind of thinking about it. And you just mentioned that you were with communities and other people. So do you think that being around those communities kind of helped you hear the languages more? Would you say that played a role in your absorption and your integration later on?

Sean:

Oh yeah. It helped because you go there, you go shopping there, talk with the people there and hear how they speak and imitate them. Sometimes they're friendly enough, they'll correct you. “No, this is how we say it…” like that. So it helped a lot that way.

Michelle:

Yeah. So I see on your bio, but I've also seen you post online that you, I don't know the exact number, but it's some really just insane number. I think of languages that you said you've achieved conversational fluency in X number, and also you've studied, I think, close to 60 languages total.

Sean:

I studied 65 languages, and I am conversationally fluent in 21 of them. Of those 21, I've mastered 10 of them. And that's another thing is the importance of language. Families. Languages are related to each other. So for example, I learned Spanish, then I can do Portuguese, Italian, Romanian, and French and Catalan.

Sean:

A bunch of segues there…

Michelle:

For sure. And I also see that with many of my friends who are romance language natives. And so when they can absorb in a way that I can't because I just didn't have the cognitive kind of predisposition, I suppose because of the fact that, yeah, I'm a native English and Mandarin speaker. Those are… English is kind of…we're at the end of the line. I could have used something that was a little bit earlier in the tree. But I'm wondering, do you just tell people that? Do you just go out in the street like, Hey, oh yeah. Well, because I've studied 65 languages, do you just say it like this or how do you present it?

Sean:

No, I keep that down low because I've learned early that people don't like a bragger, even though I tell them, see now I just say, Hey, with this method I developed, anybody can learn any language and true the way it's presented. I don't say how many languages that I've studied or can speak unless I am specifically asked. So otherwise, I kind of keep it down a little bit. Nobody likes a bragger and they probably think I'm telling a lie. Who knows?

Michelle:

But, well, I mean it's objectively, I think impressive, number one. Number two, let's talk about your method. Your it's the speak up with the exclamation point. Okay. So The Speak Up! Method.

**Sean holds up the book**

Michelle:

Yeah. Okay. The blur is on, so you might have to hold it up a little longer. We caught one second of it. Hold up. We see. Yeah, there we go. So tell us about this.

Sean:

Well, that's like I mentioned earlier, that's the method that I worked on. Basically, at first, I was looking at words, and those were simple changes in spelling or whatever can do that. But then I started looking at the grammar, and you know how it is with a language learning textbook, all those grammar rules and exceptions to the rules. And sometimes some don't even make sense. Why is, I mean, “agua” in Spanish should be “la agua,” but it's “el agua”...

Sean:

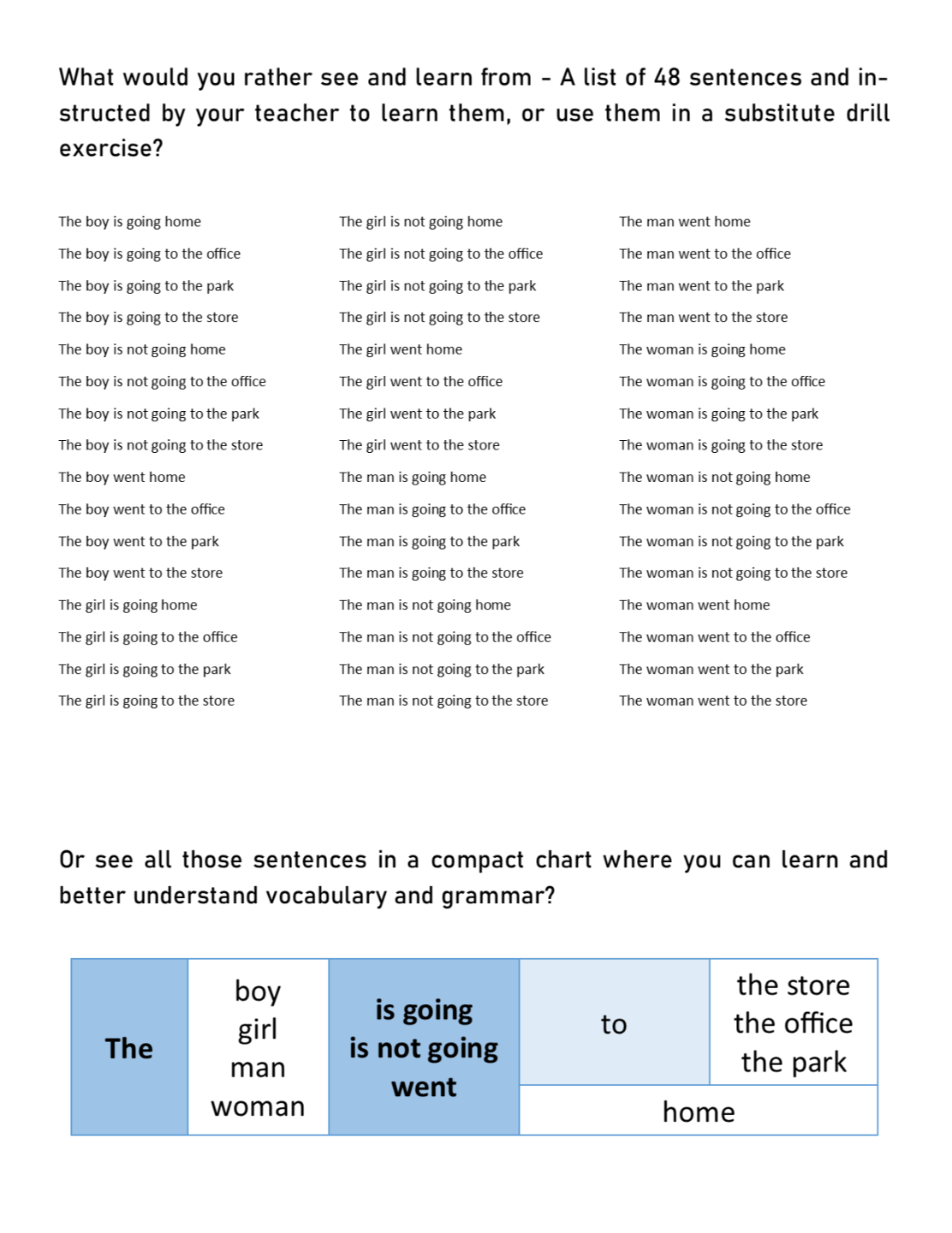

It's a feminine word with a masculine article. So all of that, I got to thinking why. So I looked for ways to eliminate grammar, basically, most grammar I should say. And this method that I chose in the chart method, it has a way of showing you how to, for example, I dunno how well you can see this.

Michelle:

Oh, I can't see that. That is, the blur is totally covering. But you know what? You can take a picture. I'll add it into the show notes. [SEE THIS TABLE ON THE EPISODE PAGE]

Sean:

I'll add it in. But anyway, I developed a chart method that takes the most important parts of a sentence into a block. And then there's other parts of that chart where the vocabulary will be interchangeable. For example, the boy is going to the store. You can change that around the boy, the girl, the man, the woman is going to the store, or they're not going to the store, but to the office, to the park or home. Maybe they are going, they're not going. They already went. Just those little changes can fit into a chart so that you can actually have, I got one chart method shown in the book here where you can have 14 vocabulary words and create over 190 sentences. And that chart makes it compact, but it's easy to see vocabulary in context rather than a list. It's a lot easier to learn it that way. And because it's that way, the grammar is already there.

You don't have to learn the grammar for that particular way of saying a sentence. You would say, I would… fill in the blank. You don't have to think about the grammar to say, I would just say I would like… etc.

Sean:

That's what I did, just getting rid of grammar. And it makes it a lot faster that way.

Michelle:

Yeah. What's really kind of interesting is that a few years back when I was trying to integrate into French society and I was not having a lot of help from local people, I wasn't really able to get into what the language was and what I was missing. Yeah. I studied where I was required to study Spanish in high school, I guess, and I chose it as my foreign language, but we all know that we choose it, we pass the test, but we don't actually know how to speak it. And Spanish itself is not French. We talked about just now how it's related, but as someone who never even really mastered in any way, Spanish, French was a whole different world. And it was in my head so impossible until I actually did something that is very, very similar to what you just described, putting in a table and having, I don't know, variable pieces.

Michelle:

Because at some point I was like, I can't do this anymore. I can't have these books telling me that I need to memorize this rule, and then I need to go and make one sentence specific for this exercise. I was going crazy. I was like, I need to communicate to (real) people. I need people to live and survive. And so I ended up just opening an Excel spreadsheet and I was like, okay, what are we working here? What's going on? Okay, subject. Okay, verb. Okay, object. Right. And so I did actually keep the grammar in, but I did switch out each individual piece to sort of make it a more natural way to look at the sentence structure or anything else. This is just one very small part of overlap between my personal random approach of survival, and you're a published book. But I do think it's very interesting. It kind of reflects the, I don't know, very natural way of wanting to find solutions that are not traditional approaches. And so I think let's kind of discuss that too, because a lot of our online interactions and also our private conversations have been about how broken traditional education is on languages. Can you just share your overall thoughts and also tell me why. How do you think we got here? Why do you think we're here?

Sean:

Where do we begin? Yeah…

Michelle:

Let’s settle in…!

Sean:

Basically the modern American educational system started back in the early to mid 18 hundreds when, what was his name? Horace Mann started to look at education, but he was also looking at it at the times that he was living in where industry was just starting in America, the industrial revolution. And so what was needed was people to learn the very basics, reading, writing, arithmetic, how to do this, how to do that. And he based the American, the education system on that, put 'em in classrooms, teach them the very basics they need to do whatever needs to be done to get out there in the world.

Michelle:

So for efficiency, was that really the idea? Get the knowledge in, get the people what they need to do whatever job or create a life…?

Sean:

To get workers out there. But the only problem is over the decades, technology has entered the curriculum. Different or different teaching learning methods are introduced, classroom layouts and the way language is presented to the student or any materials. But there's one thing that has not changed at all, and that is the way students are taught and learned. Because basically the teacher, you got the classroom with a rose, teacher's in the front teacher talks, tells you this, this, and this, and then the student has to do rote memorization or repeat ad nauseum. Oh, I remember my Latin teacher over and over and over. (Sean rattles off Latin words) I hated that. But I mean, basically the method of teaching and learning has never changed since that time. But the world is changing today, and that's part of my book under the teaching, how to make the classroom more efficient. I mean, the American education system really is outdated. It's antiquated. And so I've been trying, and I have seen some teachers and even entire school districts take my advice and change their classrooms to what I do. And they do see a marked improvement in the students, their grades, their learning, how much they learned, and how quickly they learned it.

Sean:

So it seems like now that's kind of plateauing and settling down a little bit. So people are looking at it, why we got apps. We prefer the traditional methods. It's the wrong way to do it now. I mean, I'm not blaming the teacher, I'm not blaming the teacher. They are just part of the system, which… the system is kind of broken.

Michelle:

And I was just thinking you talk just now a lot on the American education system. It's something that I also see in other countries. It's something like everyone kind of drank from the same well, or so I don't know. I don't know what was happening hundreds of years ago. None of us were here. I don't know how these decisions were made, but I do know that eventually what we have in our world now, we have all of these, what we consider traditional methods that appear very similar. The idea of forcing knowledge, input into teachers here, students, they're almost like, I am giving you food. You must eat right. This type of very authoritative approach. We see the bad, we see the rather not bad, but the non-functional, the outdated, the irrelevant. I don't know. Are there other examples of good? Are there examples of classroom learning that is a little bit more on the innovative side, but not innovation for innovation's sake, but functional, appropriate?

Sean:

I think the gold standard for education teaching students and students learning is in Finland, their educational system. Oh man, it is the best that I have seen. It's beautiful from what I've seen, they do not give tests, no examinations, no quizzes.

Sean:

They don't do that because they know such things, stresses the student out and can cause frustration. So therefore, they give the student the materials. The student learns and bounces off each other. The teacher is there to guide them in case they get stuck. I mean, I talk about this in my book too, that if the student or the group they're with gets stuck, the teacher will guide them to the answer without giving them the answer.

They'll ask open-ended questions, kind of use logic and reasoning, and that's what is needed. So I think Finland should be the gold standard in education.

Michelle:

Yeah. Yeah. It's not exactly the same, but I am a huge supporter, I suppose, of the Socratic method as an educational concept, more so in university settings and whatnot to facilitate discussion, to sort of get people involved in a way that does not rely on point A goes to point B, goes to point C, goes to, okay, memorize this and it be tested on it. Because that is actually, I mean, what we're talking about is language and the subject of language per se, but this applies to everything. I studied psychology, I studied biology. I have a dance degree I don't even talk about, and it's not like I (only) danced for that degree. Essentially—you (also) have to understand what, dance literature and arts literature and history and whatnot… philosophy. But all of those times I was in those classes. I essentially was never given… well okay, kind of in the science world, but very rarely, at least in the place I was educated, was I given: “Okay. Memorize this. Do that.” Even when I took Spanish, it was, okay, we got to work together. We got to figure it out. Here's an activity, here's a scenario. It's in context. We're beyond the stage of spoonfeeding information and then testing you on that spoonfed material.

Sean:

Yeah, because whether the teacher's up there telling you what to say and how to say it and when to say it, yeah, you're telling me, but give me time to use it. And a lot of times, well, in any subject, like you said, well, except maybe shop class, you're using hands-on, but still trying to think of, yeah…but the other academic subjects I should say, it's like it's just the teacher's doing a lot of the work basically that the student should be doing.

Michelle:

Yeah. Well, I mean, I don't know if I can even say it's work. I know that there are some teachers who for sure… they put a lot of work into it… many, many teachers, to be honest. But there are some that show up, open their book to page 15, and then read off page 15, and then test on page 15. We all go through similar education systems. I would say, when it comes to language, so you go in the classroom, everyone sits down. Why do some have that reaction of, okay, whoa, this is not going to be where I'm learning for real. It's going to be where I'm learning for tests and others. I do think they grow. They become adults. Then they start to, they want to pick up another language and they're like, oh, I have to go back to books. I have to go and hack my brain with Duolingo. I have to go and see how I can optimize it for myself. So much better now. So I don't know if you have any thoughts on this kind of an open-ended question, but what are the differences on that learner level? Why? (I mean) It's the same environment, right?

Sean:

Yeah. It'd be the same environment. It's just that, I guess it depends on the person, their capabilities, their interests, and I guess that “can do” attitude, but, and sometimes it comes in surprising ways. There are times when I've had students like, “yeah, yeah, okay, fine. I'll do this, I'll do that, whatever.” And man, they were super geniuses with language and stuff. They just picked it right up! But yeah, I guess it just depends on them and probably their environment too. If they're surrounded by people saying, sure, that sounds great. You could do that.

Michelle:

A background support system outside of the classroom that can then put it in context. Yeah…

Sean:

I've seen people get shot down because, “Hey, I'm going to learn German. Oh, but German is such a tough language. You see, those words are like this long.” I'm like,

Michelle:

Yeah, why are you stopping someone before they even start, right?!

Sean:

Yeah. I mean, it's like don't discourage them! Well, even on social media, “oh, Chinese is so hard Arabic, it's impossible. This is so hard.” I'm like, no, it's not! It's the method or the way you're choosing that makes it hard. I saw actually a thread today that said that I never believed Chinese was so easy to learn. I'm like, Hey… actually….

Michelle:

There are no tenses. Oh my God, what a gift!

Sean:

But it's like that with any other subject. I guess you can do that with math or literature or even like you said with dance, it might look hard to the beginner, but once you get into it, it just gets easier as you go along.

Michelle:

I think what we're kind of honing in on is this idea of access and how your point of entry into learning anything, be it a language, be it a skill or anything. I think that what's shocking to me as I look online and as I hear people around me, especially a lot of my friends with kids, they're trying to find the best way for such a whatever… kid to learn whatever language and immersion and whatnot. It's a little bit strange how everyone is competing for the best way. And I am, as you know, with all the material I put online, I'm very, you have to create your best way. You have to create your own way. You can't be asking anyone else, and I suppose I feel so strongly about this because of what you're talking about. Every person is different. Every person's brain, every person's mind and their own identity and how they choose to go through their life will be different. And even what worked for them when they were younger doesn't mean it's going to work now, or it doesn't mean it's going to be relevant for their adult lives or their jobs. Let's talk a little bit about the stuff that online is worth Myth busting a little. So one that comes to my mind is this idea that there are people good at learning languages and people bad at learning languages. Bust this for us, okay? Please!

Sean:

That's not true! Haha everybody started the same way. We're all born knowing nothing. The only thing that makes a person, the only thing that makes a person good at languages or bad at languages is up here. If you hear Arabic being spoken and you got that sound, and people are like, what? It's like the back of the throat there. The K sound back of the throat, and they're like, well, that's impossible. I can't do that. I go, yes, you can. English has that sound. They're like, how do I go? Say the word coin, pay attention where your tongue is coin. It's right there. Exactly. For the Arabic sound. I mean, nobody is a genius with languages. Nobody is, how can I say this? Challenged at languages, basically. It's just how much work and effort you put into it. I mean, I've seen some people work at it and work at it, and they're slowly getting there, but they think they're bad at learning languages by telling them, no, there's a Chinese proverb: Don't worry about going slow as long as you keep going. And people will hit a plateau in their learning and they'll say, “Oh, I can't get any further.” I go, here's what you do. Stop learning. They're like, what? For two or three days? Put down your books. Do not look at anything. Nothing. Your brain is full of information. It needs to reset. Put everything where it belongs and everything. Now, I'll guarantee within a few days you'll be fresh and you'll be ready to go again. And sure enough, that's what happens.

Sean:

Nobody's bad. Nobody's good at learning languages or learning anything. It's just how to do it, how to pace yourself, how to find a way that works for you, because the way I learn languages is not the same as you and vice versa. We just got to find our own way to do it.

Michelle:

And doesn't mean there can't be overlap. You can have some similar approaches for, I was just talking with a friend who is struggling with subjunctive in Spanish, and granted, I don't even remember if I learned it in Spanish. I did have to teach it to myself in French, and I had a conversation with her and essentially talked about, okay, here's how I conceptualize it. Maybe it'll work for you. I don't know. I'm going to just tell you what worked for me, how I thought about it, how much I just ignore, to be honest, for French grammar, how much I'm like, okay, whatever. What is the verb? Okay, then, so we're just going to do this. Right? But I really do think it's kind of this message that hopefully over time, hopefully with more podcasts, hopefully the Sean & Michelle Show will come out, and we'll talk a lot more on these topics.

(Sean signals his enthusiasm at the camera)

Michelle:

I know! But we can really, really push back on this idea that you're just naturally predisposed to being good or bad. It is really shocking to me actually, that there are people who really believe it, and they allow that narrative to shape. And it's not just for people who think they're bad. It's also people who think they're really good at learning something. Had a friend who, oh, can't really talk about this in a lot of detail here, but had a friend who was her partner, thought that he was great at some language, and then ended up visiting the country where that language is spoken and realized his whole life, telling people that he was amazing at this and that he was so good and he was basically native. Yeah. Got shot down the first interaction. So I do think those stories are really powerful. Okay we're going to take a quick break to reset our Zoom link because we were going to need to, but I will just meet you back here!